I contend that wronged women do not die. They live on as witches, goddesses, spirits, echoes and stories. In the Quran, murdered girls speak in the hereafter too. The book of books says that on the day of judgement a female infant will ask, ‘For which crime did you bury me alive?’

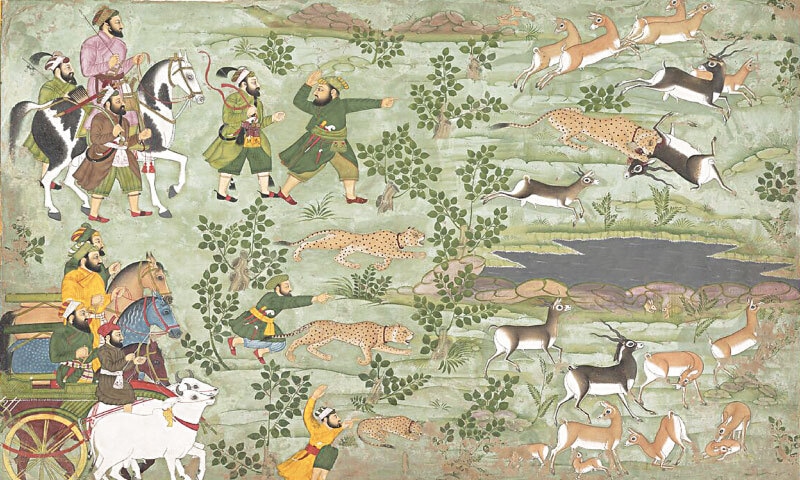

I was working on an index of thematically similar entries across codices when the order was given: keep an account of the imperial hunt. I am no storyteller. Still, a royal command cannot be denied. If the same skills that brought me to sanctuary in the Great Moghul’s Kitabkhana, the largest house of books in the world, now bind me to the page to record the adventures of the hunt, so be it.

To question the Great Moghul is to question why the sun rises in the east, why a lion hunts, why a daughter of Iblis cannot be trusted. I have packed into a leather satchel all the things I need: balms, oils, potions and other concoctions. Nibs like needles, paper thin as a fly’s wings, powder that can be mixed with spit to make ink — implements to fashion miniature texts like this one.

I will set down what I can of the words and deeds of Amar Singh the warrior, Jingu the tracker and Qamaruz Zaman the artist as we travel through the greatest empire in the world, on the trail of the wondrous beasts it contains. Courier pigeons will carry these missives back to the one who sends us, the one I address, the one I hope to please. If he notices this lowly one at all in these pages, may he notice it as one notices the stirring of grain in a sack when a mouse passes.

In 16th century India, a team of four — a warrior, a tracker, an artist and a mysterious

narrator — have been sent by the Great Moghul to record the imperial hunt in his vast

dominions. Their first assignment is to trace a beloved royal court elephant that has

gone rogue. Eos presents, with permission, an excerpt from Ferdowsnama, the latest

novel from Shandana Minhas, recently published by Penguin India…

Maya was the Great Moghul’s most beloved elephant. In times of war, she was tethered close to him, covered in matching metal armour, ready to execute the enemies he sentenced to death. She crushed their heads and removed their limbs with poise and refinement. In times of leisure, she moved with him, dressed in matching finery, from Delhi to Zikri to Nagra to Lahore, and all the minor stars in his dazzling necklace of cities too. She marched behind him in the imperial convoy as it wound through the plains and mountains, valleys and deserts, of the land of many rivers.

The breastplates of the war elephants Maya marched between reflected the gems in her silk and velvet caparisons, her chains of thick gold. Maya’s ears were pierced with sapphire studs, and her iron anklets flashed emeralds. Yak tails brushed smooth hung from the gold filigree net draping her forehead. The net was wrought by the same goldsmiths who served the harem.

Maya’s diet was in line with her status. She ate roots and grasses gathered while dew formed on them and drank from freshly scoured barrels. The fruit offered to her was grown in rosewater. Any bull in the stable who did not please her was sent to a battlefront and not allowed to return; any that pleased her was allowed to please her.

At the time of their union, Maya and her chosen mate were honoured by the presence of the Great Moghul on a lattice-covered platform in the wall of the breeding pen. The Great Moghul was accompanied by a chosen begum clad in a gold filigree face covering and anklets matching Maya’s, with the night’s constellations hennaed on to her skin. Of such pleasure was Maya’s first calf born in Lahore.

A Nath Jogi on the other side of the fire interrupted them. Pulling at his dhoti, he asked if the merchant had heard the Punjabi epic Heer Ranjha. The merchant was sad to say he only knew of the love story so far. He hoped to hear it on this tour and take it back with him too. Did Qamaruz Zaman have knowledge of a translation of it from Punjabi into Persian? Qamaruz Zaman said he was sure the Kitabkhana’s translators were working on it. Surely the merchant knew the Great Moghul had all the stories circulating through his empire recited to him? Then he had the ones worth sharing translated into its many tongues so his subjects could know them too.

Shortly after the birth of her calf, Maya began to move away when the calf tried to nurse. She began rolling up her trunk at delicacies, pacing circles into the elephant ground by the Ravi. She grew restless on walks through Lahore’s gardens. The animal hakim and astrologer spent days poring over Maya’s chart and faeces. They advised a change of scenery as Scorpio moved into Mars.

But the weather was turning. The Great Moghul did not want to leave the warmth and security of his fort and harem or abandon the daily banquets in which alliances were made or renewed or the Thursday symposiums in which Hindus, Muslims, Jews, Sikhs, Zoroastrians, Jains, Jesuits and those wholly without a sense of the Creator debated metaphysics and exchanged opinions on more mundane matters, such as how and when to pray, or when it was acceptable to conceal one’s faith from other people. He ordered that Maya’s chains be unfastened, her enclosure opened, so she and the calf could wander at will.

Mother and calf ambled through the courtyard where elephant fights took place, down the sloping ramps between Lahore Fort’s massive stone walls and out of its gates, past the brick-and-wood houses of the rich, through the thatched mud-brick shanties of the poor clustered around them like ticks, and into the countryside. They meandered through fields, villages, waterways and wilderness with only two mahouts for company.

Messages were dispatched back to Lahore at regular intervals to bring the Great Moghul news of the elephant he cherished more than all the others. The winter winds blew harder, but the only concerning news of Maya was that she would not accept a caparison or let one be thrown over her calf. Then, some weeks after they left Lahore, a message came. The calf had been taken by a muggermuch on a bank of the Sutlej, and a madness had come upon Maya.

The calf was frolicking in the sun-dappled shallows of the river alongside some water buffaloes when the crocodile rose and snapped its spike-toothed jaws shut on its trunk. The buffaloes scarpered up the bank as the crocodile dragged its prey under the silty water. Maya charged in till only her eyes were visible above the opalescent green, casting her trunk about till she felt a long, scaled body. She wrapped her trunk around it and backed on to the riverbank, pulling the reptile’s scaled, elongated torso and limbs with her.

The crocodile’s head remained under water as it tried to thrash free. The mud on the banks was gouged by their titanic struggle. Maya flapped her ears and, swiftly shifting her grip to the crocodile’s tail, moved alongside its body, so that it was bent like a bow, and then she knelt. Her own tail aloft and vibrating, she lowered her great head as if in worship and pressed her knees into its back. The reptile’s spine snapped.

When it stopped moving, Maya wrapped her trunk around its belly and pulled the rest of it out of the water. The thin trunk of her calf emerged last, still trapped in the reptile’s jaws. Nothing remained below the calf’s front legs. While she had battled one crocodile, others had ripped it apart.

Maya waded into the river and cast her trunk through its cold, murky depths but found nothing. She came out of the water flapping her ears and trumpeting. The mahouts who had tended her since infancy approached, making soothing sounds. She tossed them aside. They rose into the air like messenger birds carrying ominous news and fell nearby. Both took the measure of Maya’s mood and tried to stagger upright and run in opposite directions, but the mud grasped at their bare feet. Maya was upon them in no time. She laid one flat on the ground and trod on his head so it popped. She took the other by an arm and smashed him against the trunk of a cypress, which remained elegantly impassive.

She then turned her attention to a makeshift washing platform further down the bank and the women watching from the rocks there. Terror broke their paralysis, and they fled up the incline from which a clear, swift stream fed the river. Maya tackled the rocks like a goat till she was among them. We have this account from the sole survivor of that carnage. Maya’s depredations along the waterways of the Punjab since have left no others. Our newly formed company leaves the Kitabkhana tomorrow to investigate her rampage. It will be my first time outside it since I was brought here.

Jingu left Delhi on foot in the darkness. Amar Singh, Qamaruz Zaman and I left at first light. We travelled rapidly, changing horses at imperial posts where Qamaruz Zaman collected the messages waiting for us, chatted with strangers and plotted the next leg of our journey. Amar Singh spent his time washing, cleaning his weapons or bathing in the hammam if there was one.

At our first stop, I followed him into the hammam. I took off the soft cotton cloak that covered me from neck to ankle, and the leather sandals and layers of socks covering my gnarled feet. I began unwrapping the strips of pus-pocked muslin around me, beginning at the neck. I saw Amar Singh blanch. I did not take this to heart. I look at trees denuded in winter, each dry seam and crack exposed, and know I am not alone.

I hear Qamaruz Zaman calling you, Amar Singh said.

I rewrapped the muslin, pulled my socks and sandals back on and went outside. Qamaruz Zaman was nowhere in sight. I did not enter the hammam again. When Amar Singh emerged, I heard him tell Qamaruz Zaman to tell me to conduct my ablutions away from the rest of us. Why me? Qamaruz Zaman asked. Because you seem to enjoy acting like you are the leader, so you can enjoy doing the difficult parts of leading too, Amar Singh replied. But Qamaruz Zaman did not need to tell me.

At the next stop, and at each one after that, I remained with our supplies, ignoring the looks and the offerings, till one of the others came back, then went off on my own. It took us four days and three nights to catch up with Maya.

On the last leg of the journey we took to the mighty Sindhu. A fisherman took us down the wide, seemingly placid river along which the busiest trade route in the empire runs. We stepped from his small craft on to a thin pier leading up to a gate into the caravanserai at Kot Layya. The evening sky’s blush was deepening into the purple that floods the skin of poisoned men. The caravanserai was small but well-constructed.

A wall three man-spans high surrounded a paved courtyard lined with stalls for animals and, in opposite corners, a kitchen and private quarters for those who could afford them. Bigger gates, with a watchtower over them, were flung open on the other side of the courtyard. An open-air dormitory ran along the ramparts on either side of the watchtower. The caravanserai was already packed and more people kept entering.

The din of birds settling for the night rose from the thick forest of sheesham, acacia, mulberry, neem and babool visible through the gates on the other side. The din competed with the sound of the hollow rhino horn a guard on the ramparts was blowing to remind people who were still in the forest: Hurry! Hurry!

As the gates began to close, we joined others circling the courtyard looking for a place to bed down. The stalls were full. Fleeing families were packed in with livestock and goods. Goats, sheep, mules and horses jostled for space with pot-bellied children and potters, weavers, traders, farmers and herding dogs. Men packed the baked brick staircase up to the ramparts hoping to find a rope bed and count the stars.

I followed Qamaruz Zaman and Amar Singh as they considered the food and drink on offer, soaking in the sights, sounds and smells. There was barbecued meat, grilled vegetables, puffed grain offerings, baked and fried fish and bread, chicken roasts and stews, sanbusas stuffed with lentils, potatoes or mince, jaggery-sweetened grain, and a variety of beverages to beat the evening chill.

Qamaruz Zaman bought us clay bowls of fish stew and bread with coins from the purse he’d been the first to hold out a hand for, back at the Kitabkhana. Qamaruz Zaman stroked his salt-and-pepper handlebar moustache upwards, wiped crumbs from his pocked chin, flicked the thick brocade of his yellow embroidered silk coat upwards and seated himself on a plump cushion close to a fire presided over by a Persian merchant.

At his signal Amar Singh and I sank cross-legged on to the bare earth close by. I slipped a teardrop of elixir into my bowl. The merchant was taking his family on a tour of the Great Moghul’s empire, about which they had all heard so much in Isfahan. He was curious about the indigo and marigold stains on Qamaruz Zaman’s fingers.

Behind us, slumped beside the open gate of a stall guarding their bales, two traders from Xinjiang were discussing the fall of the Ming Empire in a little-known Chagatai dialect. One had heard the deposed ruler had successfully killed his consort and two daughters before hanging himself from a tree. The other had heard the youngest daughter survived having her arm lopped off, and that the new ruler was personally supervising her recuperation from the blood loss. He wanted to preserve the bloodline and legitimise his own throne. They expressed themselves freely, thinking nobody around them would be able to understand their dialect. If the daughter had indeed survived… to think of a daughter of the Ming line so dishonoured! It would have been better if her blood had nourished a seed of vengeance.

Amar Singh noticed me cocking my head towards the traders and whispered to ask if I could understand what they were saying. It was only the second time since we were bound together in the Kitabkhana that he had directly addressed me. I told him the traders were attempting to answer that ageless philosophical question: of what use is a maimed woman?

After the joke, I provided a concise and accurate summary of their exchange. Amar Singh was happy with my efforts. He chuckled at my joke and put out a hand to pat me on the back. He could not disguise the discomfort that flashed across his swarthy, striking face when his long, calloused fingers felt the ridges of my shoulder. He kept his black eyes trained on my brown ones. His long, thick lashes were petals to black irises. Where my lashes should have been, scar tissue radiated out like spokes from a wheel. The heat of Amar Singh’s hand warmed my shoulder. It was a good payoff for a bad joke and an adequate translation.

There were other benefits too. Amar Singh had witnessed my facility with languages. He had seen that under the scar tissue I was a man just like him, with a man’s understanding of the world, a man’s appetites and a man’s humour.

Qamaruz Zaman remained engrossed in conversation with the Persian merchant, stopping only to admire the merchant’s young daughter, who had emerged from the nobles’ quarters, with an attendant — a large, foul-smelling dog with matted brown fur — trailing her. The dog’s antecedents were impossible to trace. Even its eyes were different colours.

The girl was my height but still wore her inky hair in two plaits, a tactic that enabled her to avoid the veiling Persian aristocracy favoured, despite the fine black down coating her pale upper lip. She asked her father if she could go count the stars from the ramparts too. The merchant smiled. How could he deny his little princess anything while she was still his? The girl chained the dog to a ring, which was bolted into a wall close to the nobles’ quarters, and leapt up the staircase. The elderly attendant pursued, trying to throw an embroidered chador over her like a net.

The merchant gestured for Qamaruz Zaman to continue describing his work as a folio illustrator for an eccentric, reclusive noble. What an interesting life he must lead. The merchant did him too much honour, Qamaruz Zaman said in his courtly, refined manner. It was a quiet, uneventful life. His noble employer’s library was a small, insignificant one. The most exciting thing that had ever happened to him was a dream he’d had about being inside the imperial library. There, he had heard, scores of illustrators worked tirelessly and ceaselessly in departments dedicated to the highest spheres of knowledge and practice — poetry, astrology, calligraphy, translation, illustration, history, metaphysics, demonology, mythology and religion.

What a wonderful dream it had been! So many folios! So many parchments! So many albums! So many books! But when he woke up, he was just a small man again, in service to a small house, sent here and there to make sketches of root vegetables or berry bushes. He was only at the caravanserai to sketch a rare mushroom in the dense forest beyond the serai gates, a task he intended to begin at sunrise. How fortunate he was, after days on the road with companions as illiterate and dim-witted as his guard and attendant, to be even briefly again in cultured company. Qamaruz Zaman subtly led the Persian merchant to a discussion of his own interests, which we learnt had to do with the shortcomings and virtues of different versions of the Shahnameh.

A Nath Jogi on the other side of the fire interrupted them. Pulling at his dhoti, he asked if the merchant had heard the Punjabi epic Heer Ranjha. The merchant was sad to say he only knew of the love story so far. He hoped to hear it on this tour and take it back with him too. Did Qamaruz Zaman have knowledge of a translation of it from Punjabi into Persian? Qamaruz Zaman said he was sure the Kitabkhana’s translators were working on it. Surely the merchant knew the Great Moghul had all the stories circulating through his empire recited to him? Then he had the ones worth sharing translated into its many tongues so his subjects could know them too.

The merchant asked if it was true that the Great Moghul could not read. Qamaruz Zaman said it was. It was another sign of divine favour to him. The Prophet Muhammad couldn’t read either. The Persian said he was merely wondering how the Great Moghul decided which stories were worth telling. Qamaruz Zaman opened his mouth to answer when the Nath interjected again.

He didn’t want to dilute praise of the Great Moghul’s generosity or grace — may they fertilise the world forever — he simply wanted to know if, in the impending translation, Ranjha’s initiation into Nath ways would be treated as a calculation or a revelation. He had concerns that a less discerning audience might see the sorcerer’s path as simply a clever ruse for getting closer to forbidden objects of desire.

Qamaruz Zaman and the merchant agreed that the last thing anybody needed was a wave of ash-coated, scantily dressed, useless romantics mooning about the fields getting in women’s way. There was uproarious laughter, which stopped abruptly at the sudden beating of drums from the watchtower by the gate.

‘She’s here!’ the guard at the top yelled into the night beyond the closed gates. ‘The mad elephant’s here!’

Excerpted with permission from Ferdowsnama by

Shandana Minhas, published by Penguin India

The author is a novelist. Her other novels include

Tunnel Vision, Survival Tips for Lunatics and Daddy’s Boy

Published in Dawn, EOS, August 31st, 2025